Are you doing enough to control the risks to your employees’ psychiatric health?

-

Insight Article 10 May 2023 10 May 2023

-

Asia Pacific

-

People dynamics

-

Employment, Pensions & Immigration

It is no secret that organisations can and often do overlook the potential impact that their work can have on a person’s psychological health. This was the case for Ms Kozarov, a solicitor employed by the Victorian Office of Public Prosecutions (OPP) in its Specialist Sexual Offences Unit (SSOU). Ms Kozarov’s role in the SSOU required routine interaction with alleged victims of sexual offences and examination of explicit child pornography.

The High Court in Kozarov v Victoria [2022] HCA 12 (Kozarov) unanimously confirmed, in four separate judgments, that the OPP failed to take reasonable care of Ms Kozarov’s psychiatric health, and such breach “caused the exacerbation and prolongation of her chronic post-traumatic stress disorder and subsequent development of major depressive disorder”.1

There are many lessons to be learned from the Kozarov decision and from similar cases that followed, a summary of which is set out below.

Reasonable foreseeability of psychiatric injury

In Koehler v Cerebos (Aust) Ltd [2005] HCA 15 (Koehler), the High Court held that an indication of vulnerability is required as a precondition to finding that a psychiatric injury suffered by an employee was reasonably foreseeable.2

In Kozarov, the Respondent had implemented a Vicarious Trauma Policy (VT Policy) which expressly recognised the risk of psychiatric injury arising from the performance of Ms Kozarov’s role. Specifically, the VT Policy identified vicarious trauma as “an unavoidable consequence of undertaking work with survivors of trauma”, and “a process [that] can have detrimental, cumulative and prolonged effects on the staff member”.3

The High Court found that the Respondent was alive to the fact that the nature of the work performed by Ms Kozarov in the SSOU carried an obvious risk of psychiatric injury from exposure to vicarious trauma, as clearly evidenced by the existence and content of the VT Policy.4 In such circumstances, it was not necessary for Ms Kozarov to prove evident signs of vulnerability to establish that the risk of psychiatric injury was reasonably foreseeable as a consequence of her tenure in the SSOU.5 Rather, it found that where the work is “inherently and obviously dangerous to the psychiatric health of an employee”, an employer is duty bound to be proactive in implementing appropriate control measures to enable the work to be performed safely.6

Taking a proactive approach

While most employers are indeed aware of their respective duties under work health and safety legislation, the Kozarov decision is a timely reminder from employers to consider the psychological safety of their workers in addition to their physical safety. In Kozarov, Justices Gordan and Steward opined that the Respondent’s duty was “not merely to provide a safe system of work, but to establish, maintain and enforce such a system”.7 Their Honours echoed the findings of the trial judge in listing several measures the Respondent should have taken:

- implementation of an active OH&S framework;

- more intensive training for management and staff regarding the risks to staff posed by vicarious trauma and PTSD;

- welfare checks and the offer of referral for a work-related or occupational screening in response to staff showing heightened risk; and

- flexible approach to work allocation, including a permanent or temporary rotation into another area of work.8

The Respondent’s failure to implement any of the protective measures outlined above steered the determination of the case in Ms Kozarov’s favour. For example, the VT Policy encouraged “staff to rotate to minimise exposure to traumatic work”, however, in practice, the Respondent did not support or provide any opportunity for Ms Kozarov to rotate out of the SSOU to another division of the OPP.9

The effect of Kozarov in other cases

In Bersee v State of Victoria (Dept of Education and Training) [2022] VSCA 231 (Bersee), a high school woodworking teacher alleged that he was subjected to unreasonable and excessive workloads by his employer and as a result, suffered major depressive disorder and chronic anxiety.

The VSCA in its analysis of the Koehler and Kozarov decisions confirmed that the cases “do not represent a divergence in principle”,10 and went on to clarify that the psychiatric injury to Dr Bersee was reasonably foreseeable from the moment Dr Bersee’s class size increased from 22 to 25. The totality of the following facts was pertinent to the finding of reasonable foreseeability of psychiatric injury:

- the increase by three students was not immaterial in the context of a woodworking classroom and the Respondent in its capacity as an employer should have assessed the impact and risk of making this change;

- the Respondent had been informed by its health and safety representative that the change would have a significant impact on Dr Bersee’s faculty;

- Dr Bersee has shown vulnerability to stress caused by a change of workload in the past; and

- the nature of the woodworking class carried a risk of physical injury to both students and staff, given that students frequently used power tools requiring close supervision from the teacher.11

Although the risk of psychiatric injury was foreseeable, the VSCA ultimately found that the Respondent did not breach its duty of care as it took appropriate steps to address the risk of harm to Dr Bersee. It was relevant that the workload that Dr Bersee was required to undertake was not inherently dangerous to his mental health, and in such circumstances, it was not a breach of duty for the Respondent to refuse to reduce Dr Bersee’s class back to 22 students. It was enough that the Respondent offered Dr Bersee:

- professional development training to adapt to teaching larger classes;

- assistance from other teachers; and

- modification to his schedule so that he would have extra preparation time prior to the class.12

In Stevens v DP World Melbourne Ltd [2022] VSCA 285 (Stevens), Mr Stevens sought to appeal the decision of the County Court to dismiss his claim for damages in respect of psychiatric injuries suffered as a result of the ongoing bullying and harassment he experienced during his employment with the Defendant as a stevedore.

Although the County Court decision was delivered prior to Kozarov and Bersee, on appeal, the VSCA considered both judgments and found that the trial judge erred in rejecting Mr Stevens’ claim on the basis that he did not manifest evident signs of distress or vulnerability. Applying the reasoning in Kozarov, their Honours considered that the Defendant’s Discrimination, Harassment, Bullying and Freedom of Association Policy “specifically recognised that workplace bullying ‘may cause harm, including risks to health and safety’”,13 which in turn constituted an acknowledgement of a reasonable and foreseeable risk of psychiatric injury on the part of the Defendant.

Having surpassed the hurdle of reasonable foreseeability, the VSCA went on to state that the critical inquiry in this case should be whether the Defendant took reasonable care to avoid an acknowledged reasonably foreseeable risk of psychiatric injury being inflicted to Mr Stevens by his fellow workers in the workplace.14 The matter was remitted back to the County Court for rehearing, and a decision remains to be seen.

Key takeaways for employers

- To successfully discharge the duty to maintain a safe system of work, employers need to assess whether the work being undertaken carries a foreseeable risk of psychiatric injury or whether the risk of psychiatric illness is reasonably foreseeable.

- If it is impossible to mitigate or remove the risk of psychiatric injury, so far as is reasonably practicable, or if the employer operates in an industry that is “inherently and obviously dangerous to the psychiatric health of the employee”, employers should take a proactive approach to prevent or minimise the risks of psychiatric injury to an employee so far as is reasonably practicable.

- Employers must ensure that any existing policies dealing with potential risks to the psychiatric health of employees are appropriate in scope, regularly reviewed, implemented consistently and enforced, ensuring that workers and other duty holders are consulted accordingly.

- Careful consideration should be had when drafting policies relating to the risk of psychiatric injuries in the workplace – these policies may be relied on by the courts as evidence that employers were on notice of the foreseeable risk of psychiatric injury.

- The courts are increasingly raising their expectations when considering the responsive measures taken by employers once they become aware of, or ought to have reasonably become aware of, any instances of bullying or harassment in the workplace. Employers would be best served in undertaking an appropriate risk management approach in this regard.

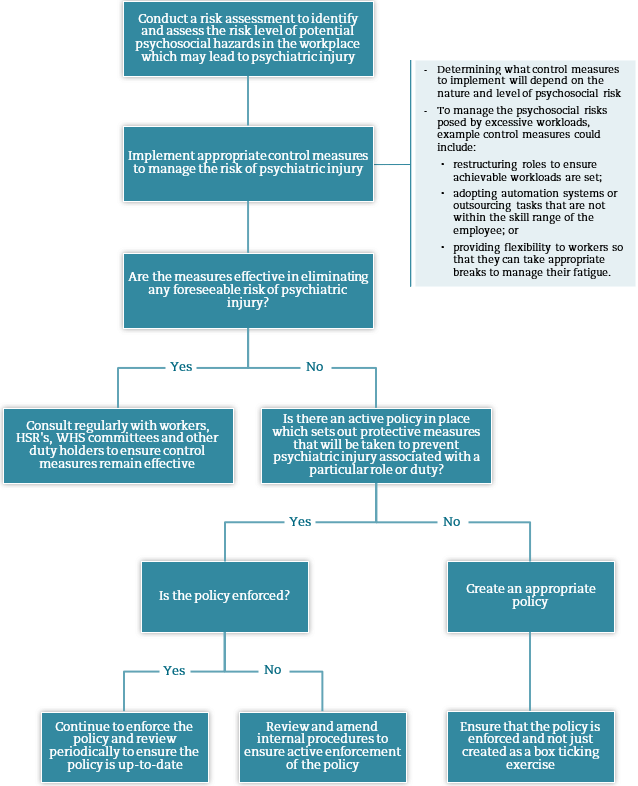

The flowchart below sets out the steps employers should be taking to manage psychosocial hazards in the workplace:

If you would like further information or advice around the tools your organisation can utilise to minimise your exposure and ensure the physical and psychological safety of your workers, please contact a member of our Clyde & Co team.

1Kozarov v Victoria [2022] HCA 12 at [65] (Kozarov).

2Koehler v Cerebos (Aust) Ltd [2005] HCA 15 at [26].

3Kozarov at [27].

4Ibid.

5Ibid at [28].

6Ibid at [6].

7Ibid at [83].

8Ibid at [82].

9Ibid at [8].

10Bersee v State of Victoria (Dept of Education and Training) [2022] VSCA 231 at [88].

11Ibid at [99] to [106].

12Ibid at [122].

13Stevens v DP World Melbourne Ltd [2022] VSCA 285 at [57].

14Ibid at [59].

End