Damages in International Arbitration: Perspectives from Egypt and Libya

Legal aspects of airport projects in Africa

-

Insight Article 05 June 2025 05 June 2025

-

Africa

-

Regulatory movement

-

Aviation & Aerospace

The twenty first century has seen a marked reduction in the role of governments in airport ownership and management, in a shift deemed as airport “privatisation”. This has been part of a broader trend towards the globalisation and privatisation of commercially driven businesses managed by the state, as well as a response to the financial difficulties states face in the development of airports.

Whilst the increased private participation in the provision of airport services can take various forms, from management contracts and concessions, to public-private partnerships (PPP), it is worth noting that these models rarely involve complete privatisation.

The movement has therefore prompted the need for clear guidance from the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) in order for countries to successfully navigate the implications of changes in ownership. Most countries that have observed the privatisation of their major airports have also established regulatory bodies to ensure that market power is not abused, particularly in the context of aeronautical charges. For example, South Africa implemented a “Retail Price Index minus X” formula to calculate aeronautical charges (where charges are capped annually based on a % of X), where the value of X is issued as guidance to the Regulating Committee.

Only 10% of Africa’s airports have been privatised. This provides an enormous opportunity for both the public and private sectors to participate in future.

The most common mode of private participation for airports in Africa, and the one on which we have focused this article, is through long-term leases or concessions. These involve a temporary transfer of services and facilities, where the government sometimes retains an equity share, for a fixed period and according to specific terms. The services and facilities are then returned to the owner when the lease expires, subject to an agreement to extend it. Countries such as Gabon, Ivory Coast, Madagascar and Cameroon have leased their largest airports to private or public companies, where they were previously managed by l’Agence pour la Sécurité de la Navigation Aérienne en Afrique et à Madagascar (ASECNA).

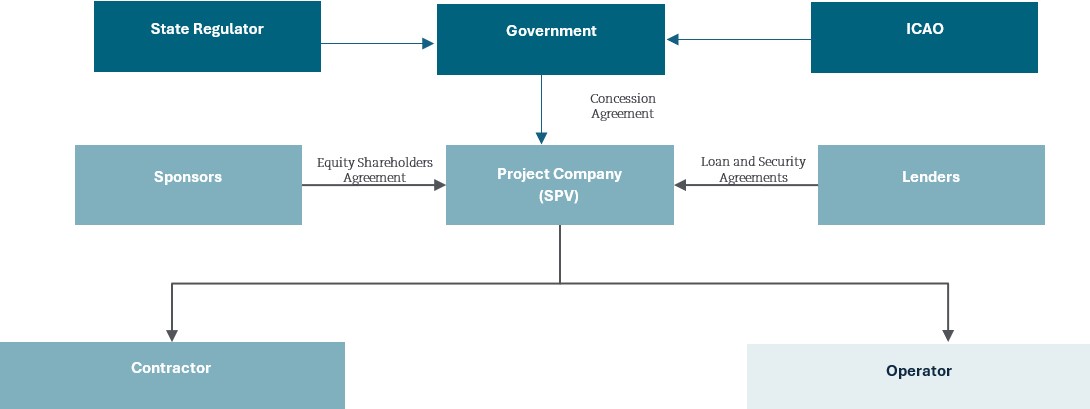

For context, we summarise below a typical airport project structure.

Planning ahead and the selection of a private provider

The Convention on International Civil Aviation is binding on all contracting states, with whom responsibility for compliance remains even where they have delegated functions to private or autonomous entities. Therefore, before considering privatisation it is essential for states to ensure that their existing regulatory bodies are suitably equipped, and to conduct a complete analysis of their aviation infrastructure, including a full profit and loss account and growth forecasts. States should also contemplate setting up an independent mechanism for overseeing airport and air navigation services, where they will continue to be economically accountable for those services. All users of the airport facilities and other relevant parties should be consulted whilst considering the change in ownership.

With regard to the selection of a private provider for the concession approach, this is usually done by way of competitive bidding. The intended involvement of the state, necessary restrictions on, and the size of individual shareholdings, should all be finalised in advance to facilitate a transparent bidding process where potential providers have all the necessary information and can have confidence in their offers. The government should clearly set out its expectations of bidders, including the structure of annual or fixed fees and the funding of any capital development programmes.

The contract document between the potential provider and the government should be carefully drafted, with particular attention paid to the government’s right to terminate the contract and resume control of the airport, and its right to impose penalties on the provider for breaches of key clauses. The contract should also specify that the legal jurisdiction of any dispute will be confined to the location in which the airport is situated and determined in accordance with its national laws.

We consider it highly advisable to seek the legal counsel of independent experts in this area, as states may lack sufficient expertise to navigate such complexities.

Key risks: Drafting and Negotiation

In this section we describe some of the key issues most relevant to major airport projects in Africa, when negotiating a concession agreement for the transfer of airport services and facilities to the lessee, or ‘Concessionaire’.

Public procurement

In the context of a privately initiated proposal put forward by the Concessionaire, it is essential to ensure that public procurement procedures are strictly adhered to from the outset. Failure to comply with procurement requirements is an existential risk for projects in Africa. We have seen procurement challenges add years to project timelines and prove damaging for governments and implementing agencies. A well-structured procurement process also allows for a proper value for money assessment and ensures the contract is awarded to a suitably qualified entity with the requisite resources and technical capacity.

Access and charging

The basis on which airport users can access the terminal and the fees to be levied need to be understood. If the Concessionaire is to take revenue risk, there will be a debate over the extent to which fees need to be regulated. The Concessionaire is likely to argue that it needs unilateral control over access and charging. The Government may take the view that it wants to satisfy objectives which are wider than maximising revenue and, in any case, that there are a number of different ways that the Concessionaire could pursue revenue maximisation. If this is the case, regulation will be required. This can often be achieved by having key performance indicators/service levels which target the parts of the operation most important to the Government and tariff review procedures which give the Government some degree of control.

Environment

The focus on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues has skyrocketed in recent years, with it now forming an essential driver for financiers, trade partners and constituents alike. The understanding of the physical, legal and transitional risks arising from the changing climate has also developed enormously. ESG considerations must be placed at the centre of the negotiation, recognising that sustainable infrastructure not only benefits the environment but mitigates risk and delivers better long term financial results.

Surrounding infrastructure

Given the strategic importance of major airports to the local economy, consideration must be given to intermodality. The airport and surrounding infrastructure (namely highways) should operate as a complete system, so that passengers and freight coming into the airport can move on to their destination speedily.

Operations

The operational characteristics of the airport may need to be specified. This would include issues such as hours of operation, capacity and parameters regarding which airlines and airplanes could be accepted. For example, if a project is intended to be constructed on reclaimed land, responsibility for undertaking land reclamation and allocation of risk for those works will need to be addressed in the concession agreement.

Risk allocation

Risk should be borne by the party most capable of carrying it, and certain trends in transferring risk to the contracting authority (the Government entity) exist in emerging markets. These include land risks (such as security, heritage and access), political risk and change in law risk. There are various measures or activities that the Government can undertake to mitigate against these, as well as the inclusion of contractual provisions to mitigate or dilute this risk for the Government.

Government risk events

In the case of a project company SPV, that entity is likely to seek protection under the concession agreement from a number of risks which it does not have the ability to mitigate or control, including changes in law or regulation, non-renewal of required consents and actions of public sector entities (such as regulators and ministries) impacting the project.

Revenue Risk

One of the key issues to be agreed up-front is how the Concessionaire is to derive revenue from operating the airport. There are two broad options: (i) the Concessionaire could generate income itself from the users of the facility; or (ii) the Government could pay a concession fee for the services the Concessionaire is providing and the Government could then retain the income generated from users of the infrastructure. In the first case, if the Concessionaire collects and retains the revenue, then it will bear the revenue risk and will want to undertake traffic modelling to satisfy itself that the scheme's revenues will be sufficient.

Project structuring

Even if the airport project is not subject to project financing, it is likely that the Concessionaire will adopt a project finance structure to ring-fence the project risk. In such a case, the Concessionaire would establish a special purpose vehicle (SPV) and the SPV would enter into the revised concession agreement with the Government (or another public sector body) pursuant to which the SPV would agree to finance and deliver the relevant infrastructure and to maintain and operate it for a number of years.

As the SPV would have been established for the purpose of the project, it would not be in a position to deliver its obligations under the concession agreement without entering into a range of sub-contracts. These sub-contracts would enable the SPV to deliver and rehabilitate the infrastructure and provide the services. The Government would need to consider the degree of oversight it requires in respect of the appointed sub-contractors.

In order to ensure the financial and technical capacity of the SPV to deliver the project, it would be essential to require some form of performance security, either from the Concessionaire’s parent company or in the form of an on-demand bond, which can be called upon in the event of a breach of its obligations under the concession agreement.

Financial considerations

It is essential for the Concessionaire that the legal and commercial terms of the concession agreement are bankable, generating a sufficient return on investment to warrant the risk and up-front capital expenditure. Equally, the Government must ensure that it obtains value for money in outsourcing a public function to the private sector.

Incentivisation

Measures can be included in the concession agreement to incentivise performance and adherence to specified standards. Incentivisation is generally managed through appointment of an independent engineer to certify construction / maintenance obligations and/or controlling or adjusting the payments which the SPV is entitled to receive. If revenue risk is transferred to the private sector, it may argue that there is no need for incentivisation as if they provide a good service, they will generate more income (and vice versa). Whilst this is sometimes the case, there may be standards which the Government would like maintained but which are not adequately incentivised simply by transferring revenue risk.

Economics of the scheme and Government priorities

Even if revenue risk is transferred to the Concessionaire, the Government will want to understand the scope of the revenue likely to be generated by the project. If the revenues are more than sufficient to finance the scheme, then the Government should expect a premium payment (fixed fee or revenue share) from the Concessionaire. It will be necessary to undertake some financial modelling to inform the Government’s approach to negotiating the revenue sharing provisions of the Concession to ensure it receives value for money and fair consideration for granting the Concession.

The Government may also consider wider policy objectives which ought to be taken into account in scoping the project which might not be captured by the Concessionaire’s economic model, even if that model is defensible on pure revenue optimisation grounds. Even if the procurement is not proceeding via a formal competitive process, the project needs to be able to withstand evaluation in terms of options analysis, affordability constraints and value for money.

Ownership, enforcement of security and insolvency regime

Due to the strategic importance of major airports, it is important that they remain operational, including in circumstances where the Concessionaire is in financial difficulty, or where third party lenders wish to exercise any security they have over the SPV or the project's assets.

This is normally addressed by giving the Government the right to terminate the concession agreement and the right or obligation to acquire the project assets. Provisions may also be included to regulate the exercise of lenders' rights if they take enforcement action against the SPV, so as to ensure that any transfer is to a suitable replacement which remains bound by the concession agreement. It is also necessary to ensure that the regime agreed between the project parties is not at risk of being undermined by third party claims against the SPV or its assets.

One option which may be helpful in this context is for the Government to retain title to the project assets (or receive a transfer of ownership in the system once completed), and to grant a licence to the SPV so it can operate the airport. This would tend to make it less necessary to protect the project assets through defensive security-taking or through creating a special insolvency regime for strategic assets.

Socio-economic considerations

Consideration should be given to the inclusion of obligations or performance measures which encourage the use of local labour and domestic contractors. This can assist in achieving any wider-ranging objectives of the Government such as a measurable increase in employment.

In places where the maintenance of airports is mandated regardless of financial viability, but based on economic, social and political grounds, governments prefer to direct funds generated from private participation to support the development of airports in financial difficulty. For example, this is the case with the major Abidjan airport in Ivory Coast.

Conclusion

When considering the overall impact of privatisation and increased participation in the provision of airports services it is crucial to account for all the stakeholders; these include not only the state and the private provider, but also the passengers, airport employees, operators and the local community. Governments tend to benefit from the transfer of ownership in that they can share out the responsibility for the development and operation of large scale airports whilst retaining a source of funds. Similarly, airport companies and airport operators see a benefit where improved efficiency increases the value of equity shares in the market.

However, there is a clear balance that must be sought when managing competing stakeholder interests. Whereas affording the state increased power may add risk to the private operator, this may also result in a higher expectation of return on investment. Furthermore, the risks incurred by governments can be controlled by well-drafted contract documents and with a robust regulatory agency and legal framework.

Please contact Peter Kasanda, Chair, Clyde & Co Africa Committee for further details.

End